"For the first time, you're more than a passive reader. You can talk to the story, in full English sentences. And the story talks right back, communicating entirely in vividly descriptive prose. What's more, you can actually shape the story's course of events through your choice of action. And you have hundreds of alternatives at every step." -Cover of several Infocom game. [1]

Introduction[]

In the world of electronic literature, Interactive Fiction is perhaps best identified by its game elements. [2] In a certain sense, Interactive Fiction literally is a game, in the sense that the reader is presented with choices and the narrative moves forward with the reader's choices. Authors themselves think of their work as writing games. [3]However, as opposed to video games, all interaction is text based. The description of place, setting, and narrative is text based, and commands are typed on the keyboard. See Computer Games and/as Literature to get a sense of the difference.

One of the many defining characteristics of postmodernism is the idea of shared authorship. [4] In its most basic sense, shared authorship is the notion that a work of literature is created by multiple parties; the author (or designer, perhaps a more accurate description) and the reader. The author puts together a framework, but the reader moves through the framework as he or she wishes, thus creating a unique experience for each different reader. Interactive Fiction exemplifies this paradigm. The author has built a framework, a world in which the meta-narrative exists. The reader tells the "author" what to do - in reality, the user interacts with the parser. (See How to Play Interactive Fiction, How to Interact or the How to Play section below.) However, the computer can be easily thought of as the author himself responding to the reader. Thus each reader has a unique experience, as the narrative is choice driven.

To be clear, this idea of shared readership is much more than simple differences in order of interaction. It is not simply that reader 1 follows path A to the end and reader 2 follows path B to the end. What makes shared authorship so powerful is that path A and path B are entirely different experiences! Readers are presented with so many choices, choices that have consequences within the narrative, that each has a completely unique experience. [5]

Here is a short video introducing Interactive Fiction:

Exploring Interactive Fiction-0

What is Interactive Fiction?[]

The Beginners Guide to Playing Interactive Fiction defines Interactive Fiction as “both a computer game and a book, or rather something in between.” [6]Interactive Fiction is a type of electronic literature that is

similar to a computer game because the player takes on the role of the main character and must use text commands to control the game and the characters. Examples of text commands are “listen” or “take it.” Please view Interactive Fiction Card for more examples of text commands. This is where the Interactive element plays a major role because the player has to tell the main character what to do in order to solve the puzzles in the game. Each time the player solves the puzzle they are able to find out more information, and the story will eventually begin to accrete meaning. Interactive fiction is similar to a book because all the different puzzles that need to be solved in the game are similar to chapters in a book which tell a story. Interactive fiction is different and unique compared to other kinds of fictions because the player determines how the plot of the game will unfold, based on how well that they play the game. It is very easy to flip through the pages of a book and find out what happens in the end, but Interactive Fiction poses a challenge for its players and requires its players to solve the puzzles to get to the end.

Interactive Fiction - "Thoughts On Interactive Fiction"

More information on Interactive Fiction

History[]

The first Interactive Fiction piece, Adventure, was created by Will Crowther in 1975. [7] Adventure was a text recreation of Crowther's spelunking expeditions in Bedquilt Cave, and he modelled the gameplay off of one of this other hobbies, Dungeons and Dragons. A Stanford graduate student named Don Woods found Crowther's work and in 1977 reworked Adventure to include fantastical elements which would be more exciting to a larger audience. [8]

'Adventure'

Interactive Fiction The Art of Video Game Storytelling-0

Watch this video on IF History!

Not long after Adventure, Interactive Fiction became commercialized. The two largest companies producing Interactive Fiction were Adventure International and Infocom. Interactive Fiction only remained commercially viable for a little over a decade, as consumer preference trended away from text-based games as technology improved. Commercial Interactive Fiction offically became 'classic' with the release of 'Classic Text Adventure Masterpieces of Infocom' by Activision in 1996. [8] [9]

The 2000's saw a resurgence of interest in Interactive Fiction as younger programmers rediscovered the genre. The web community rec.games.int-fiction, begun in 1987, was the front line of this amateur movement, and is still active today. [10]

How to Play

Beginning of game

The Gameshelf 8 Modern Interactive Fiction-0

Interactive Fiction: Guide and Examples

At the beginning of the game, the screen will provide you with an introduction. It will include background on the character you are playing as, a description of where you are, and if you are lucky some of the goals of the game. Read this text very carefully as it may give you clues about how to proceed through the game.

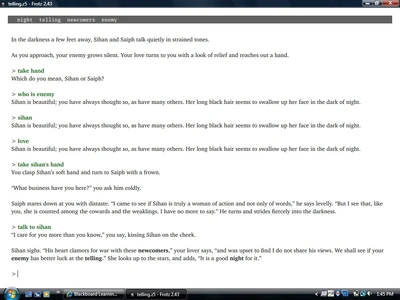

Interacting with the parser

The parser, >, is how you interact with the game and tell it what to do. You need to use imperative commands, as if actually talking to the game. Use commands to perform actions and move around in the game. After performing each task another body of text (sometimes only one line) will appear on screen in response to your command. After each command the game will prompt you with more clues that will guide you along the story. Pay close attention to the details the game provides you, as you might need them further along in the game.

Common command verbs

Look – game will give you a description of your surroundings

Examine – game will give you any helpful details of an object that you wish to examine

Search—search a location for a lost item

Take – pick up an object

Drop—put down the object

Inventory—will give you a list of what you have in your possession

Open— open something that is not locked

Close—close something

Lock—you will need a key in your possession to lock the object with

Unlock—you will need a key in your possession to unlock the object with

Ask—ask another character something or ask about something

Tell—tell another character something

Say—say something to another character

Give—give something you have picked up to someone else

Show—show something you have to someone else

Again—do the same thing again

Special Verbs:

Undo—undo last move

Quit—end the game

Restart—start game over

Save—save current game

Restore—load a saved game

Help—gives information about the game and sometimes hints to the puzzles

Wait*—take a turn without doing anything

Why do you need to command the game to wait? The game does not move forward without commands. Time does not pass if you do not interact with the parser. If you want the game to proceed without the character doing anything you must command the game to “wait.” However, this will not always help the game progress. If you are stuck on a puzzle and are trying to wait it out or wait for another clue, you will be sorely let down. The wait command usually isn’t helpful unless you are supposed to be waiting for someone to arrive, or for something to be completed before moving on to your next puzzle.

For a more in depth list of commands, please visit this website: A Beginners Guide to Interactive Fiction

Beginner IFs:

- · Colossal Cave Adventure (find a link in the above section 'History' to play)

- · Zork

- · Lost Pig

- · Ecdysis

- · Photopia

Intermediate IFs:

- · Anchorhead, the more difficult sister game to Ecdysis

- · The Hobbit

- · Spider and Web

- · So Far

Advanced IFs:

- · Suspended

- · A Mind forever Voyaging

- · Façade

- · Galatea

If you enjoy playing these games, and are interested in learning about other types of electronic texts please see hypertext fiction , digital poetry, digital games , and blog fiction .

Sources[]

<references>

- ↑ "Quotes: Interactive Fiction" [1]

- ↑ "Electronic Literature: What is it?" Section 2, Genres of Electronic Literature, Paragraph 5 [2]

- ↑ "Interactive Fiction Communities, from Preservation through Promotion and Beyond." The Form and Conventions of Interactive Fiction. [3]

- ↑ "What is Postmodernism?" Literature in a Wired World Blog, Home Page [4]

- ↑ "Sharing Authorship with Algorithms: The Challenges of Writing Interactive Stories" See paragraph about Blue Lacuna. [5]

- ↑ "A Beginner's Guide to Playing Interactive Fiction" Page 2

- ↑ "A Short History of Interactive Fiction" Article 46 [6]

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Brass Lantern, the adventure game website." A brief History of Interactive Fiction [7]

- ↑ "Wikipedia," Interactive Fiction [8]

- ↑ "rec.games.int-fiction" FAQ 1/3, Stepehn van Egmond [9]